I was browsing through the website of Anvil Publishing last February when I came across Nick Joaquin's A Question of Heroes, his collection of essays on the people who shaped our country's future and consciousness. His historical take on these heroes opened up their frailties and humanity.

I bought the book but didn't start reading it until a couple of weeks ago. I was struck by the way Nick Joaquin presented his studies. He's becoming one of my favorite Philippine Historians.

We see our Philippine Heroes through rose-colored glasses; we place them high up on pedestals. We forget that they were like us, normal folks who were thrust into circumstances beyond their control. The decisions that they made were not just products of their time but also influenced by their own personalities and nature.

Their fate was determined not just by their actions but also of the people who surrounded them. They weren't propelled to map their future because of popularity or the goal to have eternal glory but because of the genuine belief that they can do something significant that will benefit the majority.

One compelling portrait that struck me the most was all about Gregorio Del Pilar. The much revered Boy General who was pictured as a young romantic hero who sacrificed his own life in order to save his President's.

For generations of Filipinos, December has been the most anticipated month of them all. It is the most festive time of the year. Gregorio Del Pilar could not have foreseen that the 12th month of the year would prove to be both a bane and a boon for him.

As pointed out by Nick Joaquin, three major milestones of Del Pilar's young life happened in the month of December. These events left indelible marks on our history as a nation.

Familia Del Pilar

Gregorio's family belonged to an educated Bulacan family. Joaquin described the Del Pilars as "shabby gentility".

His uncle, Toribio (the brother of his father), was a vocal opponent against Friar abuses and corruption. Father Toribio was a secular priest and he was implicated in the 1872 Cavite Mutiny and imprisoned.

Toribio's younger brother, Marcelo, took up the mantle through his propagandist writings. Marcelo's nom de plume was Plaridel a play on their last name. He traveled and lived in Spain to further the advocacy against Friars meddling in civil business.

He got involved with the Katipunan through his uncle-in-law, Deodato Arellano, who served on the Supreme Council of the clandestine organization. Arellano was married to a Del Pilar sister. The Katipunan during this time was a secretive group that had chapters located in Manila, Cavite, and Bulacan. Members were recruited by family or friends.

The young Del Pilar distributed propagandist pamphlets in Bulacan as his contribution to the cause.

December 1896

The discovery of the Katipunan in August 1896 led to the start of an ill-prepared Revolution against the Spanish Regime. Two major factions within the organization emerged. One was led by Andres Bonifacio and the other was in Cavite helmed by Emilio Aguinaldo.

Gregorio Del Pilar saw his first military action in December 1896 as part of the unit of the enigmatic Eusebio Roque or Maestro Sebio in Kakarong de Sili in Pandi, Bulacan.

Gregorio Del Pilar saw his first military action in December 1896 as part of the unit of the enigmatic Eusebio Roque or Maestro Sebio in Kakarong de Sili in Pandi, Bulacan.

December 1897

The year 1897 saw his fortunes changed, he was promoted to Captain after joining Adriano Gatmaitan's army.

Goyo, as he was fondly called, saw his rise as a young Katipunan officer in the following months and because of his exploits, this brought him to the attention of Emilio Aguinaldo who promoted him from Captain to Lieutenant Colonel. after which, Del Pilar never left the side of Aguinaldo becoming part of the inner circle.

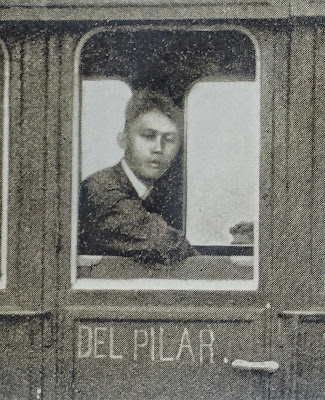

|

| Del Pilar beside Pedro Paterno and other exiles in Hong Kong |

Upon the arbitration of Pedro Paterno, Aguinaldo was convinced to have a Peace Pact with the Spanish Government accompanied by a payment of 1,300,000 Pesos.

The Biak na Bato settlement was not a popular decision among the Filipino revolutionists. Not everyone heeded Aguinaldo's call to surrender. One of the holdouts was Emilio Jacinto who continued to fight in Laguna.

With an advance of 400,000 Aguinaldo and most of the revolutionists who were loyal to him including Gregorio Del Pilar found themselves living in Hong Kong on the interest of the partial monetary settlement. Don Emilio did try to use some of the money to buy armaments to continue the cause but they were scammed.

Del Pilar's time in exile with Aguinaldo brought polish and sophistication to the young general. He even got gold fillings and braces during his expatriate days. These dental improvements would play a vital role in 1899.

In his memoirs years later, Aguinaldo described his mentorship of his protegee:

"I took him to Hong Kong, Saigon, and Singapore. He was my man of confidence. I could trust him with everything. Therefore, I had him always at my side until he died."

When Aguinaldo returned to the Philippines in the Summer of 1898 onboard an American warship, Del Pilar accompanied him. The young Goyo was a Brigadier General and together with Isidro Torres, led the resistance in Bulacan.

December 1899

By February 1899, the Filipinos were no longer fighting the Spaniards. Their new enemy was the United States of America. The ill-prepared Filipino army was pushed out of Manila in a series of battles that saw the superiority of the foreign invaders in terms of organization, arms, and professionalism among their ranks.

Aguinaldo's Revolutionary Government was plagued by patronages, intrigues, and loyalty not to the cause but to the President. Antonio Luna, the second most powerful man in Aguinaldo's Cabinet, could not instill discipline among the officers and soldiers especially those from Cavite because of Aguinaldo's indecisiveness in punishing erring troops.

Del Pilar continued to be Aguinaldo's favorite. He was assigned to plum roles and missions. He could do no wrong in the eyes of Aguinaldo but other officers thought otherwise.

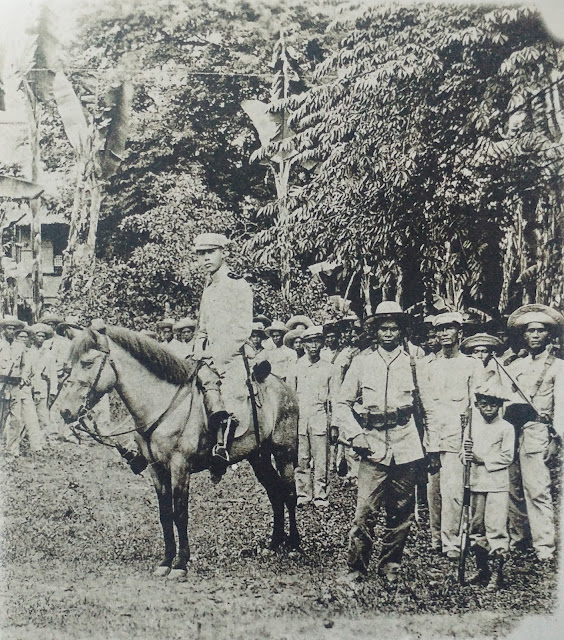

General Goyo dressed the part of a young dashing soldier. He dazzled the women with his starched uniforms and shiny boots, glistening rings on his fingers, riding on his white horse. He had a sweetheart in every town, his personal luggage was full of love letters and embroidered handkerchiefs.

Being Aguinaldo's favorite, took a toll on his relationships with his fellow officers. He was often at odds with them and at times might have shown a superiority complex. He fought with Antonio Luna and Isidro Torres (his Co-Commander in Bulacan), showing extreme loyalty and adulation to Aguinaldo.

Jose Alejandrino wrote a cryptic passage in his memoirs about a certain young general that wasn't identified:

"There was a young pretentious general who set up his headquarters in one of the nearby towns, not bothering even to present himself to General Luna. He did not want to recognize any orders other than those which emanated directly from the Captain General (Aguinaldo) of whom he was a great favorite. At the headquarters of General Luna it was learned that this gentleman spent days and nights at fiestas and dances which his flatterers offered in his honor."

|

| Antonio Luna, Gregorio Del Pilar, and other Officers. |

On the battlefield, he did not lack courage. After General Luna criticized him and his unit as 'sundalong mantika', he fought harder and engaged the enemy ferociously.

When Del Pilar joined Aguinaldo in Nueva Ecija in June 1899, he was given the mission to capture Luna, dead or alive, because of treason. He was too late because, by the next day, Luna would be assassinated in Cabanatuan.

The death of Luna on June 5, 1899, at the hands of the Kawit Regiment (Aguinaldo's personal guards), echoed the killing of Andres Bonifacio on May 1897. Their deaths would not be at the hands of the enemies but by the same Filipinos who they thought were brothers-in-arms.

A grimier task was given to Del Pilar, roundup those soldiers and officers loyal to General Luna. He relieved General Vernacio Concepcion and dismantled military units that Luna organized. He and his brother Julian arrested Luna's other aides-de-camp, Manuel and Jose Bernal. They were tortured and murdered.

From June to November 1899, Del Pilar was assigned to handle the remaining Filipino troops in Pangasinan. Aguinaldo wanted his most trusted confidante to pacify any ill-feelings that the Ilocanos might have because of the Luna assassination.

By late November, Aguinaldo would be retreating further in the mountains of the Cordillera hunted by the fast-approaching American Army. And placed the enormous task of defending the fleeing government on the shoulders of General Goyo.

When the Filipino forces learned that the Americans were in hot pursuit, Del Pilar decided to lead the defense and delay the enemy troops. On December 1, 1899, Aguinaldo and Del Pilar bid their goodbyes to each other and the younger man gallantly faced his adversary.

We're not tarnishing the memory or valor of the young general, he did sacrifice his life in order to protect the symbol of the Republic. He had an insurmountable amount of audacity and acted accordingly in the face of danger.

Our intention is not to malign but to understand better who our heroes really are. Their actions might have been dictated by the times and circumstances they lived in.

Gregorio Del Pilar's death on December 2, 1899, at the foot of the treacherous Tirad Pass was dramatized by the American Press particularly the accounts of John McCutcheon and Richard Henry Little. Their published work became the popular narrative of the Battle of Tirad Pass.

Joaquin in his book said that if ever there was an American-made hero, it would be Gregorio Del Pilar. It romanticized and may have trivialized the events of that December morning.

Vicente Enriquez, who was Del Pilar's aide-de-camp, wrote his personal testimony of what really happened during the Battle of Tirad Pass.

"I returned to the peak where I had left General Del Pilar but midway up I saw him with Lieutenants Eugenio (this should be Telesforo) Carrasco and Vicente Morales and the bugler. I told him what I had seen. The general quickened his pace on learning that the American could be seen from a certain high point. We arrived at the upper trenches. Then we went to the hilltop where I was and the moment we got there we heard renewed firing and saw our soldiers giving battle. Our soldiers, pointing with their hands, warned Del Pilar that the enemy was almost on top of us, but we could see nothing save an irregular movement in the cogon grass. So the general ordered a halt to the firing. And erect on the hilltop he tried to see and distinguish the enemy. While he was doing this he was hit by a bullet. The general covered his face with both his hands, falling backward and dying instantly. He wore a new khaki uniform with his campaign insignia, his silver spurs, his polished shoulder straps, his silk handkerchiefs, his rings on his fingers. Always handsome and elegant!"

Another account comes from Adjutant Telesforo Carrasco:

"The general could not see the enemy because of the cogon grass and he ordered a halt to the firing. At that moment I was handing him a carbine and warning him that the Americans were directing their fire at him and that he should crouch down because of his life was in danger and at that moment he was hit by a bullet in the neck and that caused instant death. On seeing that the general was dead, the soldiers jumped up as if to flee, but I aimed at the carbine at them saying I would blow the skull off the brains of the first to run, whereupon they resumed fighting while the body of the general was being removed to the next trench."

Gregorio Del Pilar's remains were plundered by the Americans. He was left naked except for his underwear. For days, his body remained in the trench until the Igorots buried him. He was recognized because of his dental braces and gold fillings.

General Goyo's glory will forever be linked with that "battle above the clouds".

Click here for References.

Comments